The cover of the December issue of Vanity Fair proclaims in large type that it's “The Art Issue.” Since the word “art” is placed right on top of Brad Pitt's crotch, you know they're not really going to talk about art. The real themes are put forth in a section of interviews called “Money on the Wall.” Here are some extracts from these interviews, which were conducted by Ingrid Sischy.

The cover of the December issue of Vanity Fair proclaims in large type that it's “The Art Issue.” Since the word “art” is placed right on top of Brad Pitt's crotch, you know they're not really going to talk about art. The real themes are put forth in a section of interviews called “Money on the Wall.” Here are some extracts from these interviews, which were conducted by Ingrid Sischy.

Tobias Meyer

(Worldwide head of contemporary art at Sotheby’s in New York.)

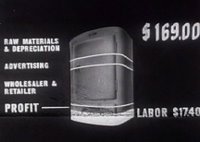

Freakonomics: “Why is it that a Rothko and a Park Avenue apartment are almost always priced the same? Now a great apartment in New York is $30 million, and now a great Rothko is also $30 million.”

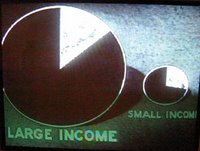

On auctions as an alternative to dealers: “…access in the contemporary-art world is...about friendship with the dealer who will give you access and let you become one of the 200 people who are waiting to buy one of these artists….But an auction is meritocratic. The one that has the most money will walk away with the desirable object that they couldn’t buy at the gallery because the gallery doesn’t know them. That’s why the auction process is so successful….”

A key reason for owing art: “The material, repeated presence of a work of art does something very different than just looking at it. Every work of art has an aura, and you can’t really experience this if you don’t have it close to you.”

On art and social critique: “Artists today don’t have any intention of reforming the bourgeoisie. They’re actually happy with it.”

Jeffrey Deitch

(High-profile art dealer in New York.)

On the attraction of the art world: “It’s social in that you see all the action around the auctions, the art fairs, the parties that go on after them. People enjoy being part of this world. It’s fun. It’s sexy. It’s a way that the hedge-fund guys can really enjoy themselves….”

On what people are buying: “People want sexy images.”

Noticing an indicator of speculation: “Now, most of the people buying really like the art. But a lot of art is also being bought and going directly to the warehouse. That is a danger sign.”

On the art market: “I think that the art market is going to be increasingly like other financial markets now that people treat it like a financial market.”

Francesco Vezzoli

(Artist based in Milan.)

On his experience at art fairs: “…I feel raped. I can be a slut, but afterwards I feel raped. It’s violent. It’s the artists deprived of any context. It’s fast food.”

Ingvild Goetz

(Art collector based in Munich.)

On the quality of art being sold: “The problem is that there is so much bad art on the market. I would say there’s very little that’s great. I would say 80 percent is not.”

‘Nice’ doesn't cut it: “…there is a lot of nice art around. I don’t like to collect nice art.”

On the worth of art: “I said, ‘Isn’t it crazy? They paid as much for a van Gogh as they would for a big plane, like a Boeing.’ He replied, ‘If you could choose the van Gogh, how could you think it has the same value as a plane. The van Gogh is worth so much more than a plane.’ ”